The Quick Take #24: Economic Astrology

An honest review of “The Myth of Capitalism,” by Jonathan Tepper with Denise Hearn.

I want to be clear, straight out of the gate, I LOVED reading this book. It forced me to assess my biases on the value of monopolies, what monopolies mean for the wider economic landscape, and how monopolies are viewed by smart people who fundamentally disagree with me. I found it to be highly thought-provoking and well researched, yet, essentially, WRONG. The complete title is, The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Competition. Tepper argues that monopolies are everywhere, and that they’re bad for society, whereas I believe that monopolies are incredibly rare and (for the most part) no worse for society than any finite resource, e.g. gold or land. We don’t work under the premise that land is bad for society, and yet plenty of smart people deem monopolies to hurt the economy. Jonathan Tepper’s work is, to my mind, an economic astrology. In the same way that star signs determine personality, to him, market share determines US economic vitality. Both relationships are based on selective evidence. I have been previously quite firm with myself that I wouldn’t write negative critiques. There is enough of that out in the world. However, I have to call attention to, what I believe to be, precarious thinking. Similar viewpoints have been used by the FTC and Justic Department to try and dismantle Big Tech, e.g. Google, so it’s important to provide an honest account of the book’s strengths and weaknesses.

Tepper is founder of Variant Perception, a macroeconomic research group, and Hearn is his Head of Business Development. As far as I can tell, Variant Perception conducts research on the economy and sells it to hedge funds, banks, and family offices. Over nine chapters, Tepper argues that competition is dying in the US. In his words:

“The battle for competition is being lost. Industries are becoming highly concentrated in the hands of very few players, with little real competition. Capitalism without competition is not capitalism. Competition matters because it prevents unjust inequality, rather than the transfer of wealth from consumer or supplier to the monopolist.”

In the first three chapters, we’re given a flurry of very useful data describing how industries are consolidating; we’re told that if businesses are not monopolized, then there’s a good chance they’re being run by colluding, oligopolies. We are then given a list of economic ills caused by monopolies, namely,

Lower wages and greater income inequality

Higher prices

Fewer startups and jobs

Lower productivity

Lower investment; and,

Less localism and diversity.

The remainder of the book dives into these topics in more detail. Chapter four makes a strong case that wages are stagnating; chapter five provides a case study illustrating the themes from chapters 1-4, describing how Big Tech is anticompetitive; chapter six lists monopolies, duopolies, and oligopolies operating in the USA; chapter seven describes how antitrust regulation has failed, and, chapter eight describes how regulation causes monopolies.

The book is chock full of data, which is a big part of why I love it. There are anecdotes throughout describing the different themes of the book (e.g. wage stagnation), and each is backed up with charts going back several decades. There are also paragraphs upon paragraphs describing businesses with dominant market share. I invest in monopolies exclusively, so having all these names in one place is like having a high quality screen for me to go through and look for ideas. Among other things, I learned that local milk refineries are monopolies, and that Monsanto controls 80% of the US corn seed market. If you buy this book, you’ll have 30 new research projects, just like that.

The negatives are more surreptitious. Tepper is a Rhodes scholar, and I’m sure he’s a lot smarter than me, but he’s falling victim to some old school survivorship bias. His book is littered with examples of traditional industries, where the remaining players have consolidated, and competitors folded. All the while, he’s ignoring new entrants with a slightly different offering. Market definitions are constantly evolving, and looking at a single, narrowly defined product over 20 years can lead you to false conclusions.

Tepper writes, “90% of US media outlets are owned by six corporations: Walt Disney, Time Warner, CBS, Viacom, NBC Universal, and News Corporation.” We all watch TV, and we all know that this segmentation is completely wrong. How can a book published in 2018 describe these businesses an oligopoly without mentioning YouTube, Netflix, and Facebook? The definition of media company has changed, distribution has changed, and old market share numbers don’t apply anymore. It’s not an isolated example. At one point, Tepper writes that “five banks control about half of the nation’s banking assets,” but he never addresses the rise of shadow banks. People use money markets (via their retail brokers) for cash management, and Americans use non-bank mortgage originators when they buy homes. The most egregious example comes from his discussion of telecoms. According to Tepper, “almost all [high-speed internet] markets are local monopolies; over 75% of households have no choice with only one provider,” and “the US cell phone market is dominated by four firms.” What he doesn’t mention is that the competitive landscape is being completely redrawn. Fiber-to-the-home is being offered by wireless companies, and cable companies are offering wireless plans. It’s a full blown price war, with parallel markets invading each other’s territory, yet the author is arguing that the industry has no competition, somehow with a straight face.1 These are just three examples of poor segmentation, but I promise you, there are many, many more.

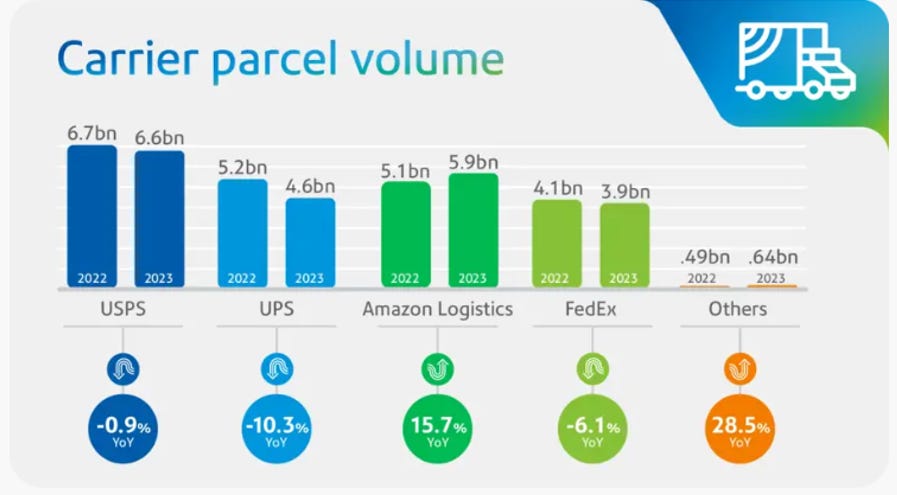

Even if Tepper’s market segmentations were perfect, he’d still be ignoring competition from suppliers. Yup, you heard that right. Suppliers are competing with their customers and vice-versa, more and more. Many of the industries Tepper calls monopolies have single suppliers, and those suppliers are expanding vertically. Entire value chains are becoming a series of overlapping “monopolies.” They may have pricing power at different points in time, but they’re extremely unstable. Amazon is my favorite example. For years, they relied on UPS for last mile deliveries. Tepper even calls UPS “a duopoly with FedEx in domestic shipping.” Too bad Tepper didn’t see the chart below.

Yup, Amazon carried more parcels than UPS in 2023. Tepper missed the fact that Bezos holds a choke point in the value chain for ecommerce (i.e. customers for unbranded goods, offered at cost). Amazon moved down the value chain and disintermediated other monopolies, e.g. UPS. Intel is another example of vertical encroachment. Tepper writes, “Intel dominates the market [for microprocessors] with around 80% share,” while also saying that “Apple’s iPhone and Google’s Android completely control the mobile app market in a duopoly,” but he ignores the fact that all three companies compete in chip design, not to mention that they’re all reliant on a single company to manufacture high-end chips (i.e. TSMC), and that TSMC is reliant on a single company to produce its high-end lithography machines (i.e. ASML). At the very least, the companies Tepper describes as monopolies regularly face pricing pressure from suppliers, if not outright existential competition.

More than anything, I take issue with Tepper’s argument that monopolies cause economic harm. He makes his argument by listing all the bad things that are happening in the economy and providing lots of data. The problem is, he’s describing correlation not causation. For example, he goes into tremendous detail showing us that wage stagnation is very real. I completely agree. But he loses me when he says that wages are stagnant because workers have to negotiate with consolidated industries. There are just so many alternate and simultaneous explanations, and they’re not discussed. My own view is that median net worth has increased at about 5% per year, over 30 years, due to home price inflation, so homeowners (about 65% of the population) are willing to forego wage increases because they’re getting rich from other assets. It’s awful for renters, to be clear, and will probably require government intervention at some point, but it has nothing to do with monopolies. This (and other arguments) are more plausible if you think that Tepper’s argument (that a handful of dominant firms control the labor market), is overstated, like I do.

Referring to a perceived decline in the number of US startups, Tepper says, “The lack of economic vitality is deeply troubling.” Then he shows a chart indicating that there are fewer new firms than there used to be as a percentage of total firms. He’s right. New firms divided by existing firms was c. 17% in the 1970’s, vs. c. 10% for exiting firms, which implies a growth rate in total firms of 7%. Today, entry and exit rates are both closer to 10%. All I know is that a 7% growth rate is completely unsustainable when population growth is closer to 1%. If there were 10 million businesses in the 1970’s and they grew at 7% for 50 years, we would have 294 million business in the US, more than the adult population! Entries and exits SHOULD be equal assuming the size of firms is unchanged over time. Again, there’s no causation established with monopolies. At the end of the day, the S&P 500 turns over every 30 years, and that’s enough to convince me that the economy is dynamic.

Most flagrantly, Tepper argues that dominant companies don’t commercialize innovation, citing the incumbents dilemma, i.e. people don’t introduce new products that cannibalize their existing products. Tepper literally says that Google kills productivity, defined by economists as GDP per hour worked. Crickets. It’s just wrong. Two Googlers just won Nobel prizes for inventing AI, which Google is commercializing to replace human coders as we speak. Google (and everyone else) knows that the ‘incumbent’s dilemma’ is real, and respond in kind. Rather than locking away innovation, they either commercialize it (as is the case with AI), or they give it away for free and adjust their business model accordingly. There’s even a name for it: open-sourcing. When Amazon had an early lead in containerization, Google made a competing product and gave it away for free.2 When Apple had an early lead in mobile O/S, they built Android… and gave it away for free. Deflationary? Maybe. Productivity killer? No way. Google is reinventing entire swaths of the economy, freeing up resources for new productive purposes, and, all the while, their core franchise is under constant threat, most recently from OpenAI and others. If this is too anecdotal for you, check out 100 years of R&D data as a percent of GDP. Spoiler alert: It’s going up. Innovation is alive and well, and I’d wager productivity improvements will revert to the mean.

Obviously there’s a lot in the book I disagree with, but you should definitely check it out.3 Tepper doesn’t shy away from big ideas, and it’s incredible food for thought. Chapter 8 is spot on. Regulation can create cause monopolies. If the government says people can’t enter a market, or makes it difficult to enter a market, incumbents benefit. I obviously think “real” monopolies (i.e., those that truly have no competition, not just dominant share), are rare, but, I like being forced to think about my conclusion in detail, and this book made me do just that. It didn’t change my mind, but it was incredibly useful. Failing that, you still get a list of (potentially) dominant businesses to study for $22.

N. B. In discussing this text, I have realized just how much there is to say on the value of monopolies. This piece was contrived to demonstrate to Tepper et al. that the world is more competitive than they expound and that monopolies aren’t necessarily bad. I could probably write a PhD thesis on the subject, so I understand if there are viewpoints and information not covered and would be so interested to hear alternate opinions and estimations. Let me know in the comments!

Check out the article below for my views on the telecom price war.

The Quick Take #2: Mutually Assured Disruption for Telecoms

I’ve been looking at Telecoms recently and it’s pretty clear that the competitive environment is shifting massively.

Check out the article below for my views on containerization.

The Quick Take #4: AWS and ITs Weakening Entry Barriers

Warning: This is a jargon filled article, which may be hard to follow if you’re new to cloud computing like me, but if you give it a chance, it’ll try to explain why IaaS is a commodity.

You’ll notice that I didn’t address “less investment,” “higher prices,” and “less localism” from Tepper’s list of economic harm caused by monopolies. I disagree (unsurprisingly) with all three assertions. Here are my high-level thoughts on the first two.

Less investment isn’t necessarily a bad thing. My gut tells me that companies are less capital intensive these days because manufacturing as a percentage of GDP is shrinking, from c. 22% in the 1950’s to 10% today. It’s not because monopolies aren’t investing. Companies are more likely to offer services delivered by humans vs. goods manufactured by machines. I’d also note that consumption of fixed capital, which is like depreciation for the US economy, looks flat as percentage of GDP.

Tepper cites research that companies increase their prices after they’ve merged, as evidence that inorganic consolidation is bad for the economy. But there’s no mention of pricing power prior to the mergers, nor to the types of businesses being merged. If local monopolies are being combined to form national monopolies, then continued price increases are to be expected. They would have had pricing power before merging, so they should continue to have it.

My newsletter is literally about monopolistic companies, so you intrigued me